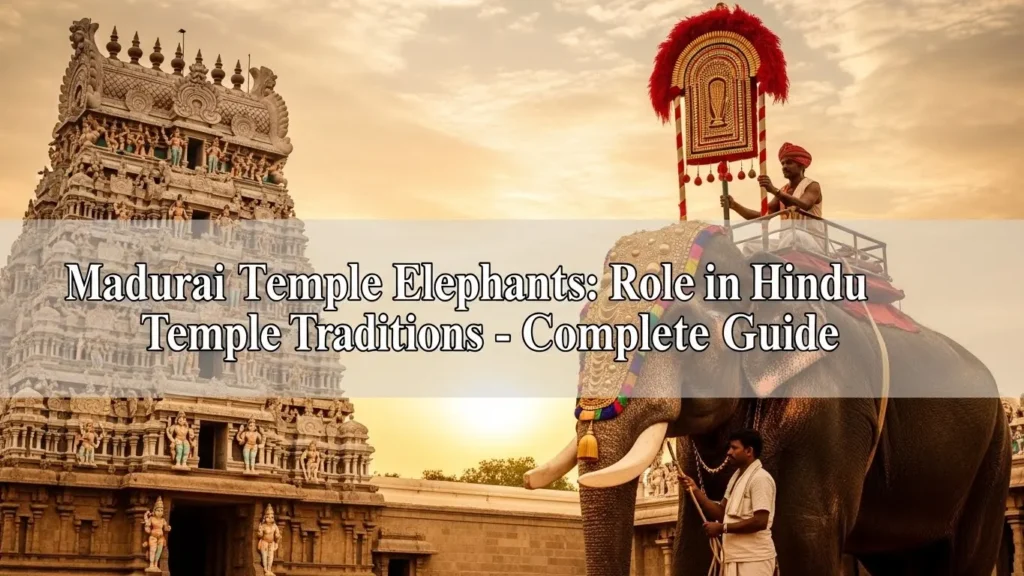

Madurai Temple Elephants Temple elephants represent one of Hinduism’s most ancient and sacred living traditions, serving as consecrated participants in daily worship, embodiments of Lord Ganesha’s divine wisdom, and living bridges between devotees and the divine across major temples in South India, particularly at the Meenakshi Amman Temple in Madurai where resident elephants like Madhuravadivu offer blessings to thousands of pilgrims daily. In Hindu culture, elephants are revered as sacred symbols for over 4,500 years, believed to embody Ganesha (the elephant-headed remover of obstacles), represent wisdom, success, prosperity, and good fortune, and serve as vehicles (vahanas) connecting the earthly and divine realms. At Meenakshi Temple,

the temple elephant stands near the entrance offering blessings by gently touching devotees’ heads with its trunk after receiving offerings of ₹10-20 or bananas, typically appearing during morning hours (7-10 AM) and early evening (5-7 PM) as an integral part of the temple’s sacred ecosystem. These gentle giants undergo ceremonial bathing, receive blessed food offerings, are adorned with garlands, colorful shabracks, and nettipattoms (ornamental forehead covers), and participate in elaborate temple processions, with their daily care mirroring the reverence given to deities themselves.

However, the tradition faces significant welfare concerns as investigations reveal that many captive temple elephants endure harsh conditions including prolonged chaining (90% chained over 9 hours daily), inadequate nutrition, confined spaces without proper ventilation, psychological trauma from isolation and festival stress, and brutal training methods, with temple elephants in Tamil Nadu spending approximately 4.5 hours daily giving 800-2,000 blessings on feast days while standing continuously.

The legendary Guruvayur Keshavan (1904-1976), honored as “Gajarajan” (Elephant King) in 1973, exemplified the ideal temple elephant through 54 years of devoted service at Kerala’s Guruvayur Temple, never causing injury despite his majestic size, winning elephant races, and refusing to let other elephants carry the deity during processions. This comprehensive guide explores the profound religious significance of temple elephants in Hindu tradition, their specific role at Madurai Meenakshi Temple, daily rituals and blessing ceremonies, training and care practices, festival participation across Kerala and Tamil Nadu, welfare challenges and modern reforms, famous temple elephants throughout history, and how these magnificent creatures embody the intersection of devotion, tradition, and evolving ethical consciousness in Hindu philosophy.

Religious Significance of Elephants in Hinduism

Ancient Sacred Symbolism (4,500+ Years)

Elephants have held sacred status in Hindu culture for over 4,500 years:

Indus Valley Civilization: Elephant seals and artifacts from the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500 BCE) demonstrate that elephant reverence predates recorded Hindu texts

Vedic Literature: Ancient Vedas and Puranas extensively reference elephants as divine creatures with supernatural qualities

Cosmic Significance: Hindu cosmology describes eight divine elephants (Diggajas) supporting the world at the eight cardinal directions, maintaining cosmic balance and order

Lord Ganesha: The Elephant-Headed Deity

The primary religious significance stems from Lord Ganesha:

Remover of Obstacles: Ganesha is worshipped before any new venture, journey, or important undertaking to remove obstacles and ensure success

Deity of Wisdom and Prosperity: Represents intellectual achievement, business success, and material abundance

Universal Worship: Perhaps the most universally worshipped Hindu deity across all traditions, sects, and regions

Elephant Embodiment: Temple elephants are viewed as living embodiments of Ganesha’s divine qualities:

- Wisdom and intelligence (elephants are highly intelligent animals)

- Strength combined with gentleness

- Ability to overcome obstacles (elephants create paths through dense forests)

- Auspiciousness for new beginnings

- Memory and loyalty (elephants never forget)

Elephants as Divine Vehicles (Vahanas)

Elephants serve as vehicles for various deities:

Indra’s Vahana: Airavata, the white elephant, serves as the mount of Indra (king of gods), symbolizing clouds, rain, and prosperity

Lakshmi’s Association: Goddess Lakshmi (wealth and prosperity) is sometimes depicted with elephants performing abhishekam (ritual bathing) with sacred water, representing fertility and abundance

Symbol of Royal Power: Kings and rulers rode elephants in royal processions, connecting earthly authority with divine legitimacy

Temple Elephants as Living Divinity

Temple elephants occupy a unique spiritual status:

Living Embodiments of Divine Blessings: Unlike mere symbols or representations, temple elephants are treated as living carriers of divine grace

Tangible Link: Create a physical connection between devotees and abstract spiritual concepts

Consecrated Beings: Through ritual consecration and continuous sacred service, temple elephants transcend ordinary animal status to become sacred beings worthy of worship

Blessing Transmission: The elephant’s trunk touch transmits divine blessings directly from the deity through the consecrated elephant to the devotee

Temple Elephants at Madurai Meenakshi Temple

Madurai Temple Elephants The Resident Elephants

Meenakshi Amman Temple in Madurai maintains resident temple elephants:

Current Elephant: The female elephant Parvathi has served at the temple, though elephants rotate and change over the years

Madhuravadivu: Another elephant that has served the temple in recent years

Naming Tradition: Temple elephants often receive names with religious significance (Parvathi, Lakshmi, Madhuravadivu, etc.)

Number: While specific numbers vary, major temples typically maintain 1-3 elephants for daily service and ceremonies

Daily Blessing Ritual

The blessing ceremony (ashirvada) forms the temple elephant’s primary duty:

Location: The elephant stands near the entrance or at a designated spot within the temple complex

- Morning hours: Approximately 7:00-10:00 AM

- Early evening: Approximately 5:00-7:00 PM

- Schedules may vary based on temple ceremonies and elephant rest requirements

- Devotee Approach: Pilgrims approach the elephant calmly and respectfully

- Offering: Devotees offer ₹10-20 notes or bananas/fruits to the mahout (handler)

- Prayer Posture: The devotee folds hands in prayer (namaste) and bows slightly

- Trunk Blessing: The elephant extends its trunk and gently touches or taps the devotee’s head

- Offering Transfer: Some elephants accept offerings directly from the devotee’s palm (following mahout guidance)

- Approach calmly—never startle or rush toward the elephant

- Offer contribution to the mahout first

- Stand at respectful distance with hands folded in prayer

- Bow slightly as the elephant extends its trunk

- Allow the elephant to initiate contact rather than reaching out

Religious Meaning: The trunk touch symbolizes:

- Ganesha’s blessing and obstacle removal

- Divine grace transmitted through the consecrated elephant

- Auspicious beginning for temple darshan

- Spiritual merit and good fortune

Daily Workload

Temple elephants maintain demanding schedules:

Blessing Hours: According to a 2010 study, temple elephants in Tamil Nadu spend on average about 4.5 hours daily giving blessings

Individual Blessings:

Standing Duration: Elephants must stand the entire time, sometimes chained to prevent movement

Physical Demand: The repetitive trunk movements, constant standing, and crowd exposure create significant physical and mental stress

Participation in Temple Rituals

Beyond blessing ceremonies, elephants participate in:

Daily Processions: Morning and evening ceremonial processions around the temple complex

Sacred Water Rituals: At Meenakshi Temple, sacred water is drawn from a well in the river and carried in procession accompanied by music and elephants

Festival Ceremonies: Major role during annual temple festivals and special occasions

Deity Processions: Carrying or accompanying the deity during important religious ceremonies

Temple Pageantry: Adding majesty and divine presence to religious celebrations

Living Conditions at Meenakshi Temple

Welfare concerns exist even at major temples like Meenakshi:

Shelter: Female elephant Parvathi’s shelter is reportedly not properly ventilated with no fan, limited free space

Urban Environment: Temple located in busy Madurai city center creates noise, pollution, and stress

Infrastructure: Many older temples lack facilities designed for elephant welfare in modern contexts

Challenge: Balancing traditional temple architecture with contemporary animal welfare standards

Training and Care of Temple Elephants

Traditional Mahout System

Mahouts (pappaan in Malayalam, kavadi in Tamil) are skilled elephant handlers:

Bonding: The training emphasizes establishing a strong bond between mahout and elephant

Specialized Skills: Mahouts teach elephants:

- Bowing or assuming “prayer posture” with trunk raised to forehead

- Standing still for extended periods during blessing ceremonies

- Participating calmly in crowded processions despite noise and chaos

- Responding to verbal commands and physical cues

- Playing musical instruments like mouth organ/harmonica

- Temple-specific rituals and movements

Traditional Knowledge: Mahout skills are often passed down through families across generations, maintaining ancient elephant-handling wisdom

Relationship: Ideally, a mahout develops a lifelong relationship with a specific elephant, understanding its personality, needs, and temperament

Training Methods: The Controversy

Traditional training involves controversial practices:

Positive Methods: Modern training centers like Kodanad Elephant Training Centre emphasize:

- Positive reinforcement techniques

- Humane methods respecting elephant intelligence

- Building trust rather than fear

- Gradual conditioning to temple environments

Brutal Traditional Methods: However, many temple elephants endure harsh breaking:

Katti Adikkal (Brutal “Ritual”):

- Male elephants are subjected to this practice annually during musth (heightened hormonal state)

- For 3-4 months during musth, elephants are constantly tied in confined spaces, unable to move

- At musth’s end, they undergo continuous beating for 48-72 hours by groups of men

- Purpose: “Breaking their will” to reassert human dominance

- Similar to the notorious phajaan (crush) method used in Southeast Asia

- Causes severe physical injury and psychological trauma

Capture and Early Training:

- Elephants are often captured as calves from wild populations (particularly Northeast India)

- Separation from mothers and herds causes profound psychological damage

- Early training may involve food deprivation, beating, and isolation

- Creating fear-based obedience rather than cooperative partnership

Daily Care Routines

Proper elephant care requires extensive daily attention:

- Daily bathing ritual, often in rivers or temple ponds

- Scrubbing with coconut husk to clean skin and remove parasites

- Elephants enjoy water play and social interaction during bathing

- At centers like Kodanad, bathing in the Periyar River is a highlight

Feeding:

- Elephants require massive quantities of food (200-300 kg daily)

- Natural diet: Tree bark, leaves, branches, grasses, fruits

- Temple diet: Often inadequate—sweets, cooked rice, jaggery, bananas, coconut

- Glucose-rich, unnatural foods cause serious health problems

- Dependency on devotee offerings rather than proper nutrition planning

Water:

- Elephants need 200-250 liters of clean water daily

- Urban temples often struggle to provide adequate quantities

- Contaminated water sources pose health risks

- Veterinary examinations and treatment

- Foot care (crucial for elephants standing on concrete)

- Treatment for injuries, infections, and chronic conditions

- Annual rejuvenation camps in Tamil Nadu provide 48-day intensive care for temple elephants

Exercise:

- Twice-daily walks to improve health and prevent obesity

- Natural movement essential for physical and mental well-being

- Temple elephants often lack adequate exercise space

Enrichment:

- Social interaction with other elephants (when possible)

- Mental stimulation through varied activities

- Play and natural behaviors

- Often severely lacking in temple settings where elephants are isolated

Adornment and Decoration

Temple elephants receive elaborate ceremonial decoration:

Daily Decoration:

- Facial paintings: Trunk, forehead, and ears painted with colorful designs

- Garlands: Fresh flower garlands around neck and body

- Nettipattom: Ornamental golden/brass covering for forehead and trunk

- Bells: One or more bells around neck or body creating musical sounds

- Shabracks: Colorful ceremonial cloths draped over back and sides

Festival Decoration:

- Even more elaborate adornment during major festivals

- Gold and jewel-studded ornaments

- Multiple layers of silk cloths

- Intricate caparisons covering entire body

- The decoration itself becomes a form of worship and offering to the divine

Significance: The adornment transforms the elephant from ordinary animal to consecrated divine presence, visually communicating its sacred status

Temple Elephants in Festival Traditions

Kerala Temple Festivals

Kerala’s temple festivals feature spectacular elephant displays:

Thrissur Pooram

Kerala’s grandest temple festival:

Location: Vadakkunnathan Temple, Thrissur

Timing: April-May (Medom month in Malayalam calendar)

Elephant Procession: The centerpiece features:

- Minimum 15 elephants per temple (Thiruvambadi and Paramekkavu compete)

- Elephants ornately decorated with gold caparisons, nettipattoms, and colorful decorations

- Arranged in magnificent rows creating spectacular visual display

- Accompanied by traditional percussion ensembles (panchavadyam, pandimelam)

- Drummers and musicians playing with religious fervor

- Fireworks displays adding to the spectacle

Competition: Neighboring temples compete to showcase the grandest elephants and most vibrant celebrations

Significance: Demonstrates the pinnacle of Kerala’s temple elephant tradition and cultural pageantry

Guruvayur Ekadasi

Major festival at Guruvayur Temple, Kerala:

Ten-Day Celebration: Featuring daily elephant processions with temple’s large elephant population (approximately 50 elephants)

Aanyottam (Elephant Race): Traditional competitive event where temple elephants race, historically won by legendary Guruvayur Keshavan in the 1930s

Seeveli Processions: Multiple daily processions with elaborately decorated elephants carrying deity representations

Other Kerala Festivals

Numerous temple festivals across Kerala incorporate elephants:

- Attukal Pongala

- Chettikulangara Bharani

- Aarattupuzha Pooram

- Machad Mamangam

- Individual temple annual festivals (ulsavams)

Tamil Nadu Temple Traditions

Tamil Nadu temples also maintain elephant traditions:

Meenakshi Temple Festivals: Annual celebrations at Madurai featuring resident elephants in processions

Kanchipuram Temples: Major Vaishnavite and Shaivite temples with elephant participation

Tirupati: Some ceremonial use of elephants at the famous Venkateswara Temple

Regional Festivals: Numerous smaller temples across Tamil Nadu incorporating elephants into annual celebrations

The Changing Landscape

Some temples are reconsidering elephant use:

Sree Kumaramangalam Subramanyaswamy Temple (Kumarakom, Kerala) made history in 2025 by:

- Ending its 120-year tradition of elephant parades

- Replacing elephants with decorated chariots in festival processions

- Prioritizing animal welfare and safety over tradition

- Using funds saved for charitable purposes benefiting the community

Significance: This progressive decision reflects:

- Growing animal welfare awareness

- Recognition of harsh conditions and safety risks

- Possibility of honoring heritage while evolving ethical practices

- Temple tradition can adapt without losing spiritual significance

Other Temples: Some temples are reducing elephant use, improving welfare conditions, or seeking alternative ceremonial practices

Famous Temple Elephants in History

Guruvayur Keshavan (1904-1976)

The most legendary temple elephant in Kerala’s history:

Birth and Capture: Born in 1904 in the forests (lived until December 2, 1976)

Gifted to Temple: On January 4, 1922, the royal family of Nilambur gifted Keshavan to Guruvayur Temple

Extraordinary Characteristics:

- Never caused bodily injury to anyone throughout 54 years of service

- Could elevate his head as high as possible for hours while carrying Thidambu (deity representation)

- Demonstrated unique devotion—when he became lead elephant, refused to tolerate another elephant carrying the deity

- Won the Guruvayur Aanyottam (elephant race) defeating the famous Akhori Govindan in the 1930s

Historic Recognition: In 1973, Keshavan was honored with the title “Gajarajan” (King of Elephants):

- First elephant ever to receive this prestigious title

- Recognized during the temple’s golden jubilee celebrating 50 years of his service

- The honor acknowledged his unmatched devotion and service

Death: Fell ill during Guruvayur Ekadasi in 1976 and nearly collapsed during deity procession; passed away on December 2, 1976

Legacy: Keshavan’s memory remains revered, representing the ideal of temple elephant devotion, strength combined with gentleness, and sacred service

Other Notable Temple Elephants

Guruvayur Temple Herd: Maintains approximately 50 elephants at any given time (exact numbers vary), continuing the tradition Keshavan exemplified

Regional Legends: Various temples across Kerala and Tamil Nadu have their own celebrated elephants whose stories are preserved in local temple histories and folklore

Modern Recognition: Contemporary temple elephants continue serving, though changing attitudes toward captivity create evolving perspectives on their roles

Welfare Concerns and Modern Challenges

Living Conditions Crisis

Investigations reveal severe welfare problems:

- 90% of captive elephants chained for more than 9 hours daily in miniscule enclosures

- Some kept in car garages, temple rooms without ventilation, and species-inappropriate settings

- Elephants are highly social animals requiring space, movement, and herd interaction

- Permanent isolation causes profound psychological suffering

Physical Space:

- Temple courtyards and shelters often lack adequate space for natural movement

- Concrete flooring causes foot problems and joint issues

- No opportunity for natural behaviors (foraging, bathing in large water bodies, social play)

Environmental Conditions:

- Urban temple locations expose elephants to pollution, noise, and extreme heat

- Inadequate ventilation in shelters

- No access to shade, natural cooling, or forest environments elephants need

Dietary Deficiencies

Temple elephant nutrition is critically inadequate:

Unnatural Diet:

- Sweets, cooked rice, jaggery, sugarcane offered by devotees

- Glucose-rich foods causing serious deleterious health effects

- Lack of roughage (bark, branches, leaves) essential for digestion

- Dependency on inconsistent devotee offerings rather than planned nutrition

Quantity Issues:

- Elephants require 200-300 kg of food daily

- Temple elephants often receive insufficient quantities

- During COVID-19 lockdowns, temple elephants starved when devotees couldn’t visit

- Some temples cannot afford proper elephant nutrition

Water Scarcity:

- Inadequate quantity (less than 200-250 liters needed daily)

- Contaminated water sources pose health risks

- Urban water shortages affect temple elephant hydration

Psychological Trauma

Mental suffering is pervasive:

Social Deprivation:

- Elephants are highly social animals with intricate relationships in wild herds

- Captive elephants confined to permanent isolation

- Separation from family groups causes lifelong trauma

- Large crowds, noise, and bright lights create extreme stress

- Multiple male elephants in close quarters during festivals increases aggression and panic attacks

- Long working hours without rest

Health Consequences of Stress:

- Infertility

- Hyperglycemia (high blood sugar)

- Neuronal cell death

- Weakened immune systems

- Stereotypic behaviors (swaying, head bobbing)

Brutal Treatment and Musth Management

Male elephants face particularly harsh conditions:

Annual Musth:

- Natural 3-4 month hormonal period increasing testosterone

- Temple management response: constant tying in confined space, unable to move

- After musth ends, continuous beating for 48-72 hours by groups of men

- Breaking the elephant’s will through violence

- Similar to Southeast Asian “crush” (phajaan) method

- Causes severe physical injuries and psychological trauma

Incidents and Casualties:

- Regular headlines: “Elephant runs amok during temple festival”

- “Elephant crushes mahout to death” incidents

- Result of stress, inadequate rest, and brutal treatment

- Human casualties and property damage from traumatized elephants

Legal and Conservation Issues

Captive elephant management faces regulatory challenges:

Ownership Certificates: Currently 1,251 captive elephants have ownership certificates, with 723 still under process

Illegal Capture: Rules against capturing new wild elephants are “continue to be flouted”

Wild Population Decline: Indian elephant population has dramatically declined from historical numbers

Conservation vs. Captivity: Growing recognition that conservation efforts and captive welfare are spiritual responsibilities

Reform Initiatives

Various efforts aim to improve conditions:

Annual Rejuvenation Camps (Tamil Nadu):

- 48-day intensive care period for temple elephants

- Veterinary diagnosis and treatment

- Stress reduction through proper rest

- Nutritious food, good showers, twice-daily walks

- Minor health problems addressed

- Ministry of Environment and Forests guidelines on captive elephant care

- Recognition that “poor captive elephant management results in chronic suffering and reduced lifespan”

- Ethical and moral concerns about inhumane treatment

- Some temples ending elephant parades (like Kumaramangalam Temple)

- Improving living conditions and veterinary care

- Reducing working hours and festival stress

- Alternative ceremonial practices

NGO Advocacy:

- Organizations documenting conditions and advocating for reform

- Public education about elephant welfare

- Legal interventions for severely abused elephants

The Spiritual and Ethical Dilemma

Traditional Devotion vs. Animal Welfare

The temple elephant tradition creates profound ethical tensions:

Devotional Perspective:

- Elephants are consecrated beings serving the divine

- Their service earns spiritual merit and brings blessings to devotees

- Temple care is an act of devotion and honor

- Removing elephants would diminish temple traditions and spiritual experiences

- Many believe well-cared-for temple elephants live blessed lives

Welfare Perspective:

- Elephants are sentient beings suffering in captivity

- No amount of religious justification excuses abuse and deprivation

- Wild elephants in natural habitats have vastly better lives

- Tradition cannot override ethical obligations to prevent suffering

- Modern understanding of elephant intelligence and needs requires evolving practices

Hindu Philosophy and Ahimsa

The controversy raises questions about core Hindu values:

Ahimsa (Non-Violence):

- Fundamental Hindu principle advocating non-harm to all beings

- How does elephant captivity, brutal training, and confinement align with ahimsa?

- Does devotional purpose justify causing suffering?

Dharma (Righteous Duty):

- Traditional dharma includes maintaining sacred temple practices

- Modern dharma includes protecting animals and preventing cruelty

- How should conflicting dharmic obligations be reconciled?

Karma and Compassion:

- Hindu teachings emphasize compassion toward all creatures

- Belief that harming animals creates negative karma

- Can genuine devotion coexist with causing animal suffering?

Possible Paths Forward

Various solutions could balance tradition and welfare:

Improved Conditions:

- Significantly better living spaces, natural environments

- Proper nutrition, veterinary care, and enrichment

- Reduced working hours and stress

- Humane training without violence

- Social opportunities with other elephants

Alternative Practices:

- Decorated chariots or other ceremonial objects replacing elephants

- Mechanical or artistic elephant representations

- Focusing devotion on deities rather than living animals

- Maintaining cultural heritage through different means

Retirement Sanctuaries:

- Creating forest sanctuaries for aged or traumatized temple elephants

- Allowing semi-natural herd living after temple service

- Visiting programs allowing devotees to offer blessings without captivity stress

No New Captives:

- Ending wild elephant capture for temple service

- Allowing current temple elephants to live out lives with improved care

- Gradually transitioning away from the practice as elephants age

Cultural Evolution:

- Recognizing that Hindu tradition has evolved throughout history

- Modern understanding of animal sentience requires ethical growth

- Compassion and welfare can deepen rather than diminish spirituality

Frequently Asked Questions

What role do elephants play at Madurai Meenakshi Temple?

Temple elephants at Meenakshi Amman Temple offer blessings to devotees by gently touching their heads with the trunk after receiving offerings of ₹10-20 or bananas, typically appearing during morning (7-10 AM) and evening hours (5-7 PM). They participate in daily processions, sacred water rituals carried from the river accompanied by music and elephants, and major festival ceremonies. The resident elephants like Madhuravadivu and Parvathi serve as living embodiments of Lord Ganesha, representing wisdom, obstacle removal, and divine blessings for thousands of daily pilgrims.

Why are elephants sacred in Hindu temples?

Elephants have been sacred in Hinduism for over 4,500 years as embodiments of Lord Ganesha (the elephant-headed remover of obstacles and deity of wisdom), representing strength, intelligence, prosperity, and good fortune. Hindu cosmology describes eight divine elephants supporting the world at cardinal directions, maintaining cosmic balance. Temple elephants are treated as living carriers of divine blessings through ceremonial bathing, blessed food offerings, sacred adornments, and consecration rituals that transform them into tangible links between devotees and divine grace.

How are temple elephants trained?

Traditional mahout training emphasizes bonding between handler and elephant using skills passed through family generations. Modern centers like Kodanad use positive reinforcement and humane methods teaching elephants to bow, assume prayer postures, stand still for blessings, and participate in processions. However, many temple elephants endure brutal practices including Katti Adikkal—continuous beating for 48-72 hours after musth periods to “break their will,” similar to the phajaan crush method, causing severe trauma. Elephants learn temple-specific skills including playing musical instruments and responding to ceremonial cues.

What are the welfare concerns for temple elephants?

Studies reveal 90% of captive temple elephants are chained over 9 hours daily in confined, unsuitable spaces like temple rooms without ventilation. Welfare issues include inadequate diet (sweets, cooked rice instead of natural vegetation), insufficient water (less than 200-250 liters needed daily), prolonged standing giving 800-2,000 blessings on festival days, psychological trauma from isolation and crowd stress, brutal musth management, and lack of veterinary care. Tamil Nadu elephants spend approximately 4.5 hours daily blessing while standing continuously, often chained.

Who was Guruvayur Keshavan?

Guruvayur Keshavan (1904-1976) was Kerala’s most legendary temple elephant, serving Guruvayur Temple for 54 years after being gifted by Nilambur royal family in 1922. He never caused injury to anyone, could elevate his head for hours carrying the deity, won the famous Aanyottam elephant race in the 1930s, and refused to let other elephants carry the deity once he became lead elephant. In 1973, he became the first elephant honored with “Gajarajan” (Elephant King) title during the temple’s golden jubilee celebrating his extraordinary devotion.

How do devotees receive blessings from temple elephants?

Devotees approach the elephant calmly, offer ₹10-20 or bananas to the mahout, fold hands in prayer, and bow slightly. The elephant extends its trunk and gently touches or taps the devotee’s head, transmitting divine blessings. This trunk touch symbolizes Ganesha’s grace, obstacle removal, and auspicious beginning for temple darshan. Proper etiquette includes never startling the elephant, standing at respectful distance, and allowing the elephant to initiate contact rather than reaching out. Some elephants accept offerings directly from devotees’ palms following mahout guidance.

What is Thrissur Pooram and its elephant tradition?

Thrissur Pooram is Kerala’s grandest temple festival at Vadakkunnathan Temple (April-May) featuring spectacular elephant processions as its centerpiece. Neighboring Thiruvambadi and Paramekkavu temples each present minimum 15 ornately decorated elephants in magnificent rows adorned with gold caparisons, nettipattoms, colorful shabracks, and garlands. The procession is accompanied by traditional percussion ensembles (panchavadyam, pandimelam) and drummers playing with religious fervor, culminating in vibrant fireworks displays as temples compete to showcase the grandest celebration.

Are any temples ending elephant traditions?

Yes, the Sree Kumaramangalam Subramanyaswamy Temple in Kumarakom, Kerala made history in 2025 by ending its 120-year tradition of elephant parades. The temple replaced elephants with decorated chariots in festival processions, prioritizing animal welfare and safety while honoring heritage through evolved practices. Funds saved are used for charitable community purposes. This progressive decision reflects growing awareness of harsh captivity conditions, safety risks, and the possibility of maintaining spiritual significance while adopting more ethical ceremonial alternatives.

Conclusion

Temple elephants embody one of Hinduism’s most visually magnificent yet ethically complex traditions—creatures revered for 4,500 years as living embodiments of Ganesha’s divine wisdom, serving as consecrated bridges between earthly devotees and celestial blessings, yet simultaneously suffering under conditions of confinement, inadequate nutrition, psychological isolation, and sometimes brutal treatment that profoundly contradict Hindu principles of ahimsa (non-violence) and karuna (compassion). The daily sight of Madurai Meenakshi Temple’s elephant offering trunk blessings to thousands of pilgrims, or the spectacular pageantry of Thrissur Pooram’s rows of adorned elephants in ceremonial procession, creates powerful spiritual experiences connecting devotees to ancient traditions and divine grace through these magnificent creatures’ tangible presence.

Yet the investigations revealing 90% of temple elephants chained over 9 hours daily, spending 4.5 hours giving hundreds or thousands of blessings while standing continuously, subsisting on unnatural diets of sweets and rice, isolated from herd companions, and subjected to brutal “breaking” rituals during musth paint a disturbing picture of systemic suffering justified by religious tradition. The legendary Guruvayur Keshavan—who served 54 years without harming anyone and was honored as Gajarajan (Elephant King)—represents an ideal of devoted service and careful treatment, yet his era predated modern understanding of elephant intelligence, emotional complexity, and the profound psychological damage captivity inflicts on these highly social, cognitively sophisticated beings who roam vast territories in natural habitats.

The 2025 decision by Kumaramangalam Temple to end 120 years of elephant parades, replacing them with decorated chariots while maintaining spiritual significance, demonstrates that Hindu philosophy possesses the flexibility and ethical wisdom to evolve traditions without losing devotional depth—that compassion toward sentient beings and respect for their welfare can deepen rather than diminish authentic spirituality.

The path forward requires honest reckoning with the suffering temple elephant traditions have caused, significant improvements in care for elephants currently serving (proper space, nutrition, veterinary attention, reduced stress, and humane treatment), gradual transition toward alternative ceremonial practices, and recognition that the same Hindu culture venerating elephants as divine must extend that veneration into ensuring these sacred creatures live with dignity, freedom from suffering, and respect for their inherent worth beyond human religious purposes.

Temple elephants teach us that the holiest traditions must themselves be judged by whether they honor the divine compassion they claim to represent, that no amount of devotional justification excuses causing suffering to sentient beings, and that genuine spiritual evolution means having the courage to ask whether practices inherited from ancient times serve contemporary understanding of ethics, consciousness, and our dharmic responsibilities to all creatures who share this sacred earth with us.

About the Author

Kavita Nair – Cultural Heritage & Temple Architecture Specialist

Kavita Nair is an accomplished writer and researcher specializing in Hindu festivals, temple architecture, and India’s rich cultural traditions. With a Master’s degree in Indian Art History from Maharaja Sayajirao University, she has extensively documented pilgrimage sites, temple iconography, and folk traditions across India. Her work focuses on making India’s spiritual heritage accessible to contemporary audiences while preserving authentic cultural narratives.