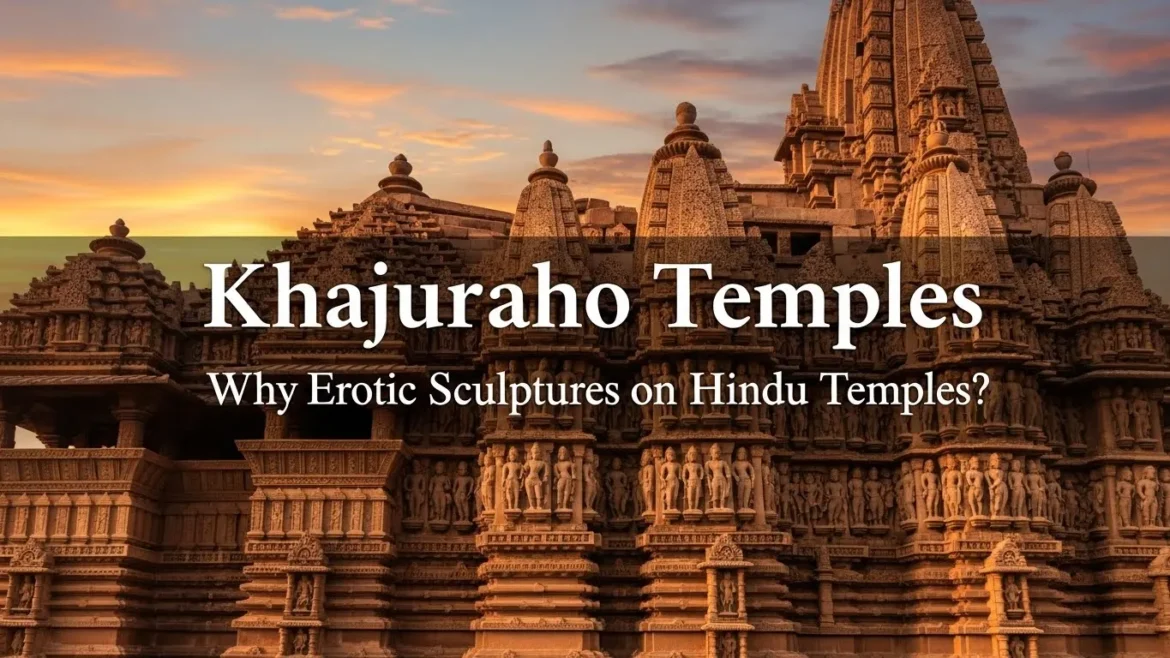

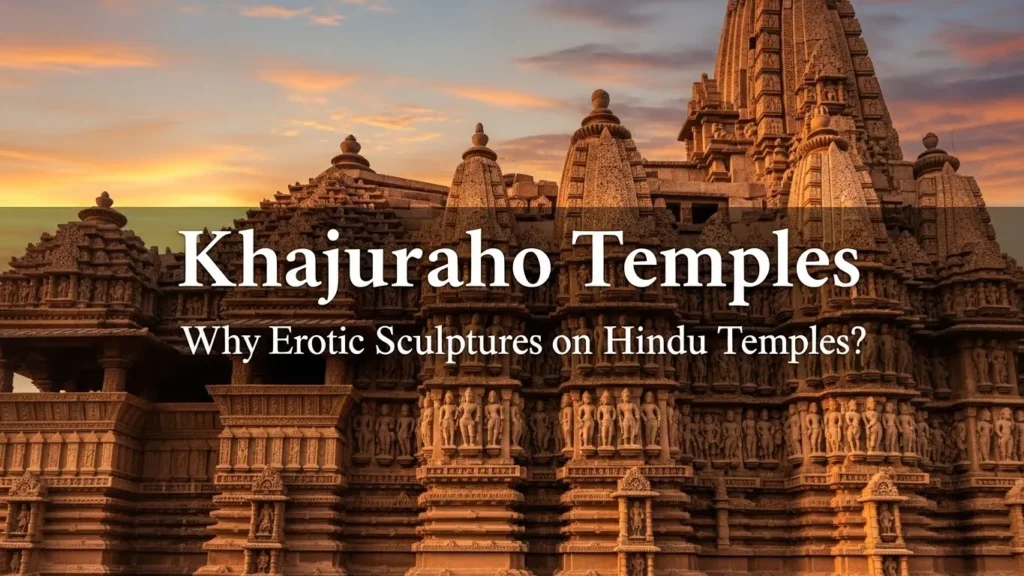

The Khajuraho Temples Group of Monuments stands as one of the world’s most enigmatic architectural treasures, where approximately 10% of the surviving 25 temples’ sculptures depict explicit sexual imagery alongside representations of gods, goddesses, warriors, musicians, and everyday life. Built between 950-1050 CE during the Chandela dynasty’s zenith, these UNESCO World Heritage temples provoke a fundamental question: why would sacred Hindu temples—spaces dedicated to spiritual transcendence—feature detailed erotic carvings showing diverse sexual positions, multiple partners, and intimate acts rendered with extraordinary artistic skill? The answer reveals profound dimensions of tantric philosophy, medieval Indian attitudes toward sexuality, and sophisticated theological frameworks that integrated sensual experience with spiritual liberation rather than viewing them as opposing forces.

The erotic sculptures serve multiple interconnected purposes—depicting the Hindu concept of Kama (desire) as one of four legitimate life goals (Purusharthas), representing tantric teachings about channeling sexual energy toward divine union, educating society about intimate relationships, testing devotees’ spiritual focus, and celebrating sexuality as sacred rather than shameful. Understanding these magnificent temples requires moving beyond simplistic moral judgments to appreciate how Hindu philosophy historically embraced comprehensive views of human existence that acknowledged bodily desires while offering pathways toward their transcendence. This comprehensive guide explores the philosophical foundations, artistic brilliance, historical context, and practical visiting information for experiencing Khajuraho in 2026.

Historical Context: The Chandela Dynasty’s Golden Age

The Chandela Rajputs ruled central India from approximately 831-1308 CE, with their kingdom reaching its zenith between 950-1050 CE when most Khajuraho temples were constructed. This period of unprecedented prosperity, military strength, and cultural flourishing enabled ambitious architectural projects that demonstrated the dynasty’s power, sophistication, and devotional commitment. Historical records indicate that 85 temples originally existed across a 20-square-kilometer area, though only 25 survive today spread over 6 square kilometers following centuries of abandonment, natural decay, and possible deliberate destruction.

Key Chandela patrons included:

- King Yashovarman (925-950 CE): Commissioned the magnificent Lakshmana Temple, one of the earliest and finest examples of Khajuraho architecture

- King Dhanga (950-1008 CE): Presided during the kingdom’s peak prosperity; multiple temples constructed during his reign

- King Vidyadhara (1003-1035 CE): Built the crowning achievement Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, the largest and most ornate structure at Khajuraho

- King Kirtivarman (1065-1100 CE): Continued temple construction tradition as the dynasty’s power began declining

The first documented Western mention appears in the accounts of Abu Rihan al-Biruni (1022 CE), the Persian scholar who accompanied Mahmud of Ghazni’s invasions and documented Indian civilization with remarkable objectivity. Ibn Battuta’s later accounts (1335 CE) also reference Khajuraho’s temples, though by this period the Chandela kingdom had collapsed under Delhi Sultanate pressure and the temple complex entered gradual abandonment. The temples’ remote location and concealment by dense forest growth ironically protected them from systematic destruction that befell many other Hindu temples during Islamic invasions.

European rediscovery occurred in 1838 when British engineer T.S. Burt stumbled upon the jungle-covered temples while conducting survey work. His reports sparked archaeological interest, leading to systematic documentation, clearing of vegetation, and eventual recognition as invaluable cultural heritage. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) initiated conservation efforts in the late 19th century, and UNESCO designated the temples a World Heritage Site in 1986, recognizing their “outstanding universal value” under criteria (i) and (iii) for artistic mastery and exceptional cultural testimony.

Understanding the Erotic Sculptures: Philosophical Frameworks

The erotic imagery at Khajuraho operates on multiple interpretative levels, each revealing different aspects of medieval Hindu thought. Reducing these sculptures to mere pornography or primitive sexual obsession profoundly misunderstands their sophisticated theological purposes and the complex worldview they embody. Scholarly analysis identifies at least seven complementary theories explaining why temples dedicated to divine worship would incorporate explicit sexual imagery:

The Purushartha Theory: Four Goals of Life

Hindu philosophy recognizes four legitimate pursuits (Purusharthas) constituting complete human existence: Dharma (righteous duty), Artha (prosperity/wealth), Kama (desire/pleasure), and Moksha (spiritual liberation). The erotic sculptures represent Kama—acknowledging sexual desire and intimate pleasure as natural, legitimate aspects of human life rather than sinful obstacles to spirituality. This framework suggests the temple’s outer walls depict worldly pursuits including sexuality, while the inner sanctum (significantly lacking erotic imagery) represents transcendence and divine union with the formless absolute.

The sequential placement communicates progression: devotees symbolically leave behind worldly attachments including sexual desire as they move from exterior to interior, from Kama to Moksha. However, the philosophy doesn’t condemn Kama but contextualizes it—sexuality has its proper place in life’s journey, and spiritual seekers can only genuinely transcend desires they first acknowledge and properly experience rather than repressively denying.

The Tantric Interpretation: Sexual Energy as Spiritual Power

Tantric philosophy, particularly influential in medieval central India including the Kalinjar region near Khajuraho, views sexual energy as potent spiritual force that, when properly channeled through specific practices, can accelerate consciousness toward divine union. The Sanskrit term “tantra” means “woven together,” reflecting the tradition’s integration of opposites—masculine/feminine, Shiva/Shakti, consciousness/energy—whose sacred union creates and sustains the cosmos.

The erotic sculptures function as visual mantras and initiation maps for tantric practitioners. The outer walls depict raw Kama in its unrefined form—ordinary sexual desire. The temple thresholds (sandhis) show transitional imagery where energy begins shifting. The inner areas lack erotic content, representing consciousness transcending bodily identification through practices that paradoxically employ sexual energy as fuel for spiritual transformation. This isn’t metaphorical—tantric texts describe specific ritual sexual practices (maithuna) performed by advanced practitioners to awaken kundalini shakti and achieve samadhi (enlightenment).

The Khajuraho temples themselves embody tantric symbolism architecturally—some scholars interpret the overall design as representing the female form or yoni (vulva), with the sanctum as the sacred womb where divine presence gestates. The vertical ascension of the shikhara (spire) symbolizes rising kundalini energy moving through chakras toward the thousand-petaled lotus of enlightenment at the crown.

The Social Education Theory: Temples as Learning Centers

Medieval Indian temples functioned as comprehensive cultural and educational institutions, not merely worship spaces. The erotic sculptures may have served practical educational purposes, visually instructing young people about sexual relationships, marriage, procreation, and the sophisticated erotic techniques documented in texts like the Kamasutra. In an era predating printed books and widespread literacy, sculptural narratives communicated essential knowledge to broad populations.

This theory suggests Khajuraho’s patrons understood that healthy societies require balanced sexual attitudes—neither repressive puritanism that generates neurosis nor unrestrained indulgence that undermines social stability. By depicting sexuality openly within sacred contexts, the temples communicated that intimate relations constitute sacred aspects of life deserving respect, artistic celebration, and proper understanding rather than shameful secrets relegated to darkness.

The Spiritual Testing Theory: Overcoming Sensory Attraction

An alternative interpretation proposes the erotic imagery deliberately tests devotees’ spiritual advancement. If temple visitors become aroused or mentally distracted by sexual sculptures, this reveals their consciousness remains bound by bodily identification and sensory attractions. Genuine spiritual practitioners should be able to view even explicitly sexual imagery with detached observation, recognizing forms as temporary manifestations of divine creative power rather than objects for personal gratification.

This framework transforms the sculptures into spiritual gauntlets—only those who successfully navigate the outer walls’ sensory temptations without losing meditative focus prove qualified to enter the inner sanctum and approach the deity. The erotic imagery thus serves protective functions, filtering out those insufficiently developed spiritually while simultaneously providing opportunities for advanced practitioners to recognize and overcome subtle attachments.

The Fertility and Continuity Theory: Cosmic Regeneration

Some scholars emphasize the sculptures’ connection to fertility, procreation, and life’s continuity. Sexual union creates new life, ensuring generational continuation and cosmic renewal. Temples representing cosmic order and divine creative power logically incorporate imagery celebrating the biological processes through which life perpetuates itself. This perspective connects Khajuraho’s erotic art to widespread fertility symbolism in global religious traditions—lingam/yoni representations, pregnant goddesses, phallic pillars—acknowledging sexuality’s sacred creative dimensions.

The explicit depictions of threesomes, group encounters, and diverse sexual configurations may reflect tantric principles about the interplay of energies or document actual ritual practices. Alternatively, they might simply represent artistic exploration of human sexuality’s full spectrum without moral judgment—a celebration of erotic diversity as divine creative expression.

The Counter-Buddhist Theory: Affirming Worldly Life

During the Chandela period, Buddhism’s influence remained significant in central India, with its emphasis on renunciation, celibacy, and transcending worldly attachments. Some historians propose the erotic temple sculptures constituted a deliberate Hindu response affirming worldly engagement, family life, and procreation as spiritually valid paths. By prominently displaying sexual imagery, Hindu temple practices asserted that liberation need not require monastic celibacy but could be achieved through the householder’s path (grihastha ashrama) that includes marital sexuality.

This interpretation views Khajuraho as ideological statement defending Hindu social structures against Buddhist critique. The temples proclaim that sex, marriage, children, and domestic responsibilities don’t inherently obstruct spiritual progress—properly contextualized within dharmic frameworks, they constitute legitimate expressions of divine will and vehicles for consciousness evolution.

The Artisan Expression Theory: Creative Freedom

The most prosaic explanation suggests the 12,000 artisans working for 12 years to construct the temples required outlets for sexual frustration while separated from families. The Chandela patrons may have granted sculptors creative freedom to channel personal desires into artistic expression, resulting in increasingly elaborate erotic experimentation. This theory acknowledges human psychological realities while recognizing that practical circumstances sometimes influence artistic production as much as theological programs.

Architectural Brilliance: Form Following Philosophy

The Khajuraho temples exemplify Nagara-style North Indian temple architecture at its most refined, with every design element serving symbolic purposes aligned with tantric and Vedantic philosophy. The temples follow the sacred Vastu-Purusha-Mandala geometric grid dividing the ground plan into 64 sub-squares (padas), with the central Brahma Pada housing the sanctum sanctorum. This mathematical precision transforms each temple into a “cosmic diagram in stone,” aligning human body, terrestrial space, and celestial order into unified sacred geography.

Major surviving temples include:

Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (c. 1025-1050 CE)

- Height: 31 meters (102 feet), the tallest surviving Khajuraho temple

- Dedication: Lord Shiva

- Features: 872 sculptures including approximately 646 exterior figures

- Significance: Represents the pinnacle of Chandela architectural achievement

- Design: Five-shrine Panchayatana layout with elaborate subsidiary temples

- Symbolism: The ascending shikhara symbolizes Mount Kailash, Shiva’s Himalayan abode

The Kandariya Mahadeva contains the highest concentration and finest quality erotic sculptures, executed with extraordinary anatomical precision, emotional expressiveness, and compositional sophistication. The sculptures demonstrate advanced understanding of human physiology, flexible body positions, and the complex mechanics of various sexual configurations. Faces display emotional states ranging from ecstatic pleasure to tender intimacy, transforming stone into seemingly sentient flesh.

Lakshmana Temple (c. 950 CE)

- Dedication: Lord Vishnu

- Patron: King Yashovarman

- Features: Raised platform (jagati) adorned with elephants, horses, battles, processions

- Style: Sandhara (with circumambulatory passage) and Panchayatana variety

- Sculptures: Seven vertical panels showing Vishnu’s incarnations; elaborate female figures

- Significance: Among the earliest and best-preserved Khajuraho temples

The Lakshmana Temple’s sculptures showcase Gupta-influenced artistic traditions with delicately carved pillars featuring scrollwork, cusped ceiling designs, and full figures of women (surasundaris) adorned with elaborate jewelry. The western exterior displays intricate erotic panels alongside mythological narratives, demonstrating seamless integration of sacred and sensual themes.

Other Significant Temples

Hindu Temples:

- Vishvanatha Temple: Dedicated to Shiva; features marriage procession scenes

- Chaturbhuja Temple: Houses four-armed Vishnu image; relatively restrained decoration

- Vamana Temple: Dedicated to Vishnu’s dwarf incarnation

- Brahma Temple: Actually dedicated to Shiva despite name; granite construction

Jain Temples (Eastern Group):

- Parshvanatha Temple: Largest Jain temple; exquisite sculptures including erotic imagery

- Adinatha Temple: Beautiful carvings of Jain tirthankaras and celestial beings

- Ghantai Temple: Features unique pillar decorated with bells and chains

The architectural progression creates deliberate spiritual journey—devotees ascend stairs to raised platforms, pass through intricately carved porches (ardha-mandapa), enter pillared assembly halls (maha-mandapa), traverse vestibules, and finally reach the womb-chamber (garbhagriha) housing the deity. This physical movement mirrors consciousness progression from worldly engagement through gradual refinement toward divine encounter, with sculptural programs shifting accordingly from erotic to devotional to transcendent imagery.

The Sculptures: Artistic Mastery and Diversity

The erotic sculptures comprise only about 10% of total carvings, though they dominate popular imagination and tourism marketing. The majority of sculptures depict:

Mythological Narratives:

- Gods and goddesses in various forms and postures

- Vishnu’s avatars including Krishna, Rama, Narasimha

- Shiva as ascetic, dancer (Nataraja), and lingam

- Goddess figures representing Shakti in multiple manifestations

- Celestial beings (apsaras, gandharvas, vidyadharas)

Daily Life Scenes:

- Musicians playing traditional instruments (veena, flute, drums)

- Dancers in classical poses

- Soldiers with weapons and military equipment

- Farmers, merchants, craftspeople engaged in occupations

- Women applying cosmetics, playing with children, conversing

- Royal processions with elephants and chariots

Erotic Imagery:

- Couples (mithunas) in standing, seated, and reclining intimate positions

- Complex configurations showing two women with one man, two men with one woman

- Group scenes with multiple participants in various combinations

- Same-sex intimacy between men, occasionally between women

- Positions from the Kamasutra and beyond, including acrobatic configurations

- Oral sex, manual stimulation, and diverse intimate acts explicitly rendered

- Human-animal combinations (bestiality) in rare panels

The artistic quality demonstrates extraordinary skill—three-dimensional forms emerge from two-dimensional wall surfaces with convincing volume, weight, and movement. Sculptors achieved remarkable anatomical accuracy in muscle definition, bone structure, and body proportions. Fabric appears convincingly textured despite being carved stone. Jewelry, ornaments, and decorative details receive meticulous attention. Facial expressions convey subtle emotions—desire, pleasure, tenderness, concentration, ecstasy.

The erotic sculptures display surprising diversity, including same-sex male intimacy depicted without apparent moral condemnation, reflecting tantric acceptance of sexuality’s full spectrum without rigid gender taboos. These representations challenge contemporary assumptions about “traditional” sexual morality, demonstrating that medieval Hindu civilization embraced considerably more expansive sexual attitudes than Victorian-influenced modern conservatism often acknowledges.

UNESCO World Heritage Designation and Conservation

The Khajuraho Group of Monuments received UNESCO World Heritage status in 1986 under criteria (i) representing masterpiece of human creative genius and (iii) bearing exceptional testimony to cultural tradition. The inscription recognizes how the temples achieve “perfect balance between architecture and sculpture” with the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple’s decorative profusion ranking “among the greatest masterpieces of Indian art”.

UNESCO criteria justifications emphasize:

Criterion (i) – Artistic Masterpiece: The Khajuraho temples represent unique artistic creation through highly original architecture and extraordinary sculptural quality. The mythological repertory includes scenes “susceptible to various interpretations, sacred or profane,” acknowledging the erotic imagery’s ambiguous nature. The seamless integration of structural design with comprehensive sculptural programs creates unified artistic statements unmatched in medieval architecture.

Criterion (iii) – Cultural Testimony: The temples bear exceptional witness to Chandella culture that flourished in central India before Delhi Sultanate establishment in the 13th century. They preserve invaluable documentation of 10th-11th century religious practices, social structures, artistic techniques, philosophical frameworks, and daily life details that would otherwise remain inadequately understood.

Conservation challenges include weathering from monsoon rains, biological growth damaging stone surfaces, tourist pressure causing physical wear, and atmospheric pollution affecting sandstone. The ASI implements ongoing maintenance including chemical treatments, vegetation control, structural monitoring, and visitor management. The temples’ relatively good preservation stems partly from centuries of protective jungle concealment followed by professional archaeological conservation since the late 19th century.

Visiting Information: Timings, Fees, and Practical Details

Temple Complex Hours and Entry Fees (2026):

Archaeological Museum:

- Timings: 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM (Closed Fridays)

- Entry Fee: ₹5 for Indians; ₹100 for foreigners

- Collection: Sculptures, architectural fragments, inscriptions, and artifacts from Khajuraho temples

Light and Sound Show:

- Venue: Western Group of Temples complex

- Languages: English and Hindi (separate shows)

- Duration: Approximately 50 minutes

- March to October Timings:

- November to February Timings:

- Tickets: ₹300 for Indians; ₹700 for foreigners

- Booking: Available online or at venue

Khajuraho Dance Festival:

- Duration: 7 days annually (typically February-March)

- Founded: 1975 to celebrate Indian classical dance heritage

- Performances: Kathak, Kathakali, Bharatanatyam, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Manipuri, Mohiniyattam

- Venue: Open-air stage with temple backdrop

- 2024 Highlight: 1,484 Kathak dancers performed simultaneously, earning Guinness World Record

- Significance: International cultural event attracting renowned artists and global audiences

How to Reach Khajuraho

By Air: Khajuraho Airport (HJR), located approximately 5 kilometers from town center, connects to major Indian cities:

- Direct flights from Delhi, Varanasi, Agra (limited frequency)

- Airlines: Air India, SpiceJet operate regular services

- Airport to temples: Taxis and local transport readily available (₹150-300)

By Train: Khajuraho Railway Station connects to several cities on the North-Central Railway Zone:

- From Delhi: Gita Jayanti Express (overnight journey, arrives ~8:00 AM)

- From Varanasi: Direct trains available

- From Agra: Rail connections via Jhansi

- Station to temples: Auto-rickshaws, taxis available (₹50-150)

By Road: Well-connected highway network enables convenient road access:

- From Agra: 400 km (6-7 hours by car)

- From Varanasi: 300 km (approximately 6 hours)

- From Jhansi: 175 km (3-4 hours)

- Bus Services: Regular government and private buses from nearby cities

- Self-Drive: Car rentals available; highways generally well-maintained

Local Transportation: Auto-rickshaws provide convenient temple transport (₹1,400 for 2-day rental including Raneh Waterfalls visit). Bicycle and motorcycle rentals available for independent exploration.

Best Time to Visit and Travel Tips

Optimal Season: October to March offers ideal conditions with pleasant temperatures (15-30°C), low humidity, and minimal rainfall. This winter period enables comfortable extended outdoor temple exploration and photography.

Season-wise Breakdown:

Winter (November-February):

- Perfect weather for sightseeing and photography

- Khajuraho Dance Festival (February-March)

- Peak tourist season; book accommodation well in advance

- Morning and evening light excellent for capturing architectural details

Summer (March-June):

- Very hot (35-45°C); early morning visits essential

- Fewer crowds; more peaceful contemplative experience

- Carry water, sunscreen, protective clothing

- Reduced accommodation rates

Monsoon (July-October):

- Heavy rainfall, especially July-August

- Lush green landscape surrounds temples beautifully

- Dramatic cloudy skies create atmospheric photography

- Minimal tourists; intimate temple experience

- Possible travel disruptions from rain

Essential Travel Tips:

- Hire Official Guide: ASI-approved guides (₹400-600) provide invaluable historical context, philosophical explanations, and point out easily missed sculptural details

- Allocate Sufficient Time: Minimum 2 days recommended—Day 1 for Western Group temples and Light & Sound Show; Day 2 for Eastern/Southern groups, museum, and nearby attractions

- Photography Considerations: Golden hours (sunrise/sunset) offer best lighting; carry zoom lens for architectural and sculptural details; respect photography restrictions in certain areas

- Dress Modestly: While temples no longer function for active worship, respectful attire appropriate for cultural heritage sites recommended

- Stay Hydrated: Limited shade at temple complexes; carry water bottles and sun protection

- Combined Attractions: Visit nearby Raneh Waterfalls (crystalline rock formations), Panna National Park (tiger reserve), and Ajaigarh Fort

- Accommodation: Book hotels/guesthouses months in advance for Dance Festival period; town offers options from budget to luxury

- Cultural Sensitivity: Approach erotic sculptures with intellectual curiosity and respect for philosophical context rather than prurient giggling

- Budget Planning: Basic visit costs ₹500-1,000 per person (entry + guide + transport); luxury experiences significantly higher

- Health Precautions: Standard India travel preparations—drinking bottled water, eating from hygienic establishments, carrying basic medications

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do Khajuraho temples have erotic sculptures?

The erotic imagery serves multiple philosophical purposes: representing Kama (desire) as one of four legitimate life goals in Hindu philosophy, embodying tantric teachings about channeling sexual energy toward spiritual enlightenment, educating society about intimate relationships, testing devotees’ spiritual focus, and celebrating sexuality as sacred rather than shameful. The sculptures reflect sophisticated theological frameworks integrating sensual experience with spiritual liberation rather than viewing them as opposing forces.

What percentage of carvings are actually erotic?

Approximately 10% of the surviving sculptures depict explicit sexual content. The majority represent gods, goddesses, celestial beings, mythological narratives, daily life scenes, musicians, dancers, warriors, and animals. The erotic carvings dominate popular imagination disproportionate to their actual numerical representation, though their artistic quality and philosophical significance justify focused attention.

Are there sculptures showing same-sex relationships?

Yes, panels depicting male-male intimacy exist, usually in group scenes within the Western temple group. These representations appear without apparent moral condemnation, reflecting tantric acceptance of sexual diversity without rigid gender taboos. The sculptures challenge assumptions about “traditional” sexual morality, demonstrating medieval Hindu civilization embraced more expansive sexual attitudes than often acknowledged.

What are the temple timings and entry fees?

The Western Group opens 8:00 AM – 6:00 PM daily with ₹30-40 entry for Indians and ₹500-600 for foreigners. Eastern and Southern groups are free and accessible sunrise to sunset. The Light and Sound Show costs ₹300 (Indians) or ₹700 (foreigners) with two nightly performances in English and Hindi. The Archaeological Museum operates 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM (closed Fridays).

How do I reach Khajuraho?

Khajuraho Airport (5 km from town) connects to Delhi, Varanasi, and Agra with limited flights. Khajuraho Railway Station offers trains from Delhi (Gita Jayanti Express overnight), Varanasi, and other cities. By road, Khajuraho is 400 km from Agra (6-7 hours), 300 km from Varanasi (6 hours), accessible via regular buses or private vehicles.

What is the best time to visit Khajuraho?

October to March provides optimal conditions with comfortable temperatures (15-30°C) and pleasant weather ideal for temple exploration. The Khajuraho Dance Festival in February-March offers extraordinary cultural experiences with classical dance performances against temple backdrops. Summer (March-June) is very hot; monsoon (July-October) brings rain but lush landscapes and fewer tourists.

How many temples survive at Khajuraho?

Twenty-five temples survive from the original 85 that existed across 20 square kilometers in the 12th century. These fall into three geographical groups—Western (largest and most elaborate), Eastern (including Jain temples), and Southern (fewer structures). The temples represent both Hindu and Jain religious traditions, demonstrating religious pluralism under Chandela patronage.

Can I attend the Khajuraho Dance Festival?

Yes, the annual 7-day festival (typically February-March) celebrates Indian classical dance forms with performances by renowned artists. The 2024 festival featured 1,484 Kathak dancers performing simultaneously, earning a Guinness World Record. Tickets available for nightly performances held at open-air venues with temple backdrops. Book accommodation many months in advance for festival period.

Conclusion

The Khajuraho temples transcend simplistic categorization as either sacred shrines or erotic monuments—they represent sophisticated integration of spiritual aspiration with honest acknowledgment of human sexuality within comprehensive philosophical frameworks. The Chandela dynasty’s architectural legacy demonstrates how medieval Hindu civilization embraced nuanced understandings of consciousness, embodiment, desire, and transcendence that resist reductive moral binaries. The erotic sculptures, far from contradicting the temples’ sacred purposes, embody tantric principles recognizing sexual energy as potential fuel for spiritual transformation when properly understood and channeled.

Understanding Khajuraho requires appreciating the Purushartha framework positioning Kama alongside Dharma, Artha, and Moksha as legitimate life pursuits requiring balanced integration rather than hierarchical suppression. The temples’ architectural progression—from exterior erotic imagery through transitional thresholds to interior sacred spaces lacking sexual content—maps consciousness evolution from worldly engagement through gradual refinement toward divine union. This isn’t repressive denial but conscious transcendence achieved through acknowledgment, experience, and ultimate movement beyond bodily identification.

The UNESCO World Heritage designation recognizes Khajuraho’s outstanding universal value as artistic masterpiece and exceptional cultural testimony. The temples preserve invaluable documentation of 10th-11th century Hindu civilization at its aesthetic and philosophical zenith, demonstrating technical mastery, theological sophistication, and cultural confidence. Conservation efforts ensure future generations can continue encountering these magnificent monuments that challenge comfortable assumptions and reveal the profound depths of Hindu philosophy and tantric wisdom.

Visiting Khajuraho in 2026 offers opportunities for genuine cultural education beyond superficial tourism. Allocate sufficient time (minimum 2 days), engage knowledgeable guides who can explain philosophical contexts, attend the Light and Sound Show for historical narrative, and if possible, experience the annual Dance Festival celebrating India’s classical arts against these sublime architectural backdrops. Approach the temples with intellectual curiosity, aesthetic appreciation, and respect for the sophisticated civilization that created enduring masterpieces still speaking powerfully across nearly a millennium.

About the Author

Sandeep Vohra – Vedantic Scholar & Hindu Philosophy Expert

Sandeep Vohra is a distinguished scholar specializing in Hindu philosophy, Vedantic studies, and scriptural interpretation. With a Master’s degree in Sanskrit and Comparative Philosophy from Banaras Hindu University, he has translated numerous Sanskrit texts and authored comprehensive commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita, Upanishads, and Brahma Sutras. His work focuses on making ancient philosophical wisdom accessible to contemporary seekers while preserving doctrinal accuracy and spiritual depth.